Measuring annual rings with your phone

Table of Contents

Part 1: Is there a need for an app to count annual rings?

When you manage your forest, age plays a big role. Are the trees too old or young to be felled? How well does your forest grow, is it time to do a thinning or is it already too late. To find out, you can either create a drill core by using an increment borer and then count the annual rings manually. You can also cut down the tree and look at the cross-section of the wood or stump. There is some PC-programs that counts the age automatically on a cross-section.

The dream would be to have a tool that you just pressed against the trunk of the tree and that counted the annual rings automatically. But there is no such tool and until then we have to solve it in another way.

We have been thinking for some time about building an app for photographing drill cores and counting annual rings.

Here is some reasons why we would build such an app:

- Several people have told me that they would really need some help with counting the annual rings.

- A lot of annual rings are counted today. The Haglöfs Company has said that they sell 5,000 increment borers annually.

- It is difficult to calculate the age of drill cores, sometimes a magnifying glass is needed.

- Camera technology in mobile phones has improved a lot in recent years.

- It would be a fun challenge to build such an app.

What speaks against building an app is:

- It will be difficult to get a working business model for an app like this. It is unclear what forest owners and forest companies are willing to pay for an app like this.

- It is a very niche product, the number of users will never be very large.

- It is always more complicated than you first think.

There is some pros and cons but we think that we will make a try because of:

- We are bootstrapped and resource efficient.

- We are a small team, with experience in building mobile applications.

- We have thousands of users of our other apps, some of them are probably interested in being able to count annual rings. We should thus be able to reach out to potential users.

To minimize the risk of building an app that provides small value to users, we intend to build it in two steps.

The first step

is to build an app to photograph annual rings and count them manually with some digital support. By tagging each image with name and GPS position, you can collect data in the forest and then count the annual rings later. It will be a so-called MVP (simplest possible product that provides value for the user).

The second step

is to count the annual rings with ai. If we collect some pictures from drill cores photographed with the app, we can use it to train an ai. Today, there are pc-software that calculate annual rings on polished cross-sections of a tree.

Drill cores are not as pleasant to use because they are dirtier and more uneven. Therefore, it will be a technical challenge to succeed in this.

Part 2: Drill Core Images

The advances in camera technology in today's phones have replaced our ordinary phones. We have started to build an app to count annual rings on drill cores on your iPhone. The first step is to test the camera and learn more about how to get the best images.

To get great pictures of the drill core, they need to be:

- Sharp

- Have high resolution

- Have even lighting

By having many sharp pixels per mm that are under even light conditions will give us good opportunity to count the annual rings.

Camera specifications for different iPhone models

The results are taken from official specifications, data from Apple's APIs and images taken by the Camera app Halide, an app that we highly recommend.

| Model | Lens | Min Focus Distance (Observed) | Min Focus Distance (Apple) | Aperture | FOV | Pixel per MM (Observed) | Pixel per MM (Apple) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| iPhone 17 Pro Max | Ultrawide | 20 mm | 20 mm | 2.2 | 106.2 | - | - |

| iPhone 17 Pro Max | Wide | 145 mm | 200 mm | 1.78 | 72.04 | - | - |

| iPhone 17 Pro Max | Tele | 750 mm | 1160 mm | 2.8 | 14.3 | - | - |

| iPhone 16 Pro | Ultrawide | 20 mm | 20 mm | 2.2 | 106.2 | - | - |

| iPhone 16 Pro | Wide | 155 mm | 200 mm | 1.78 | 72.04 | - | - |

| iPhone 16 Pro | Tele | 900 mm | 1350 mm | 2.8 | 16.4 | - | - |

| iPhone 15 Pro Max | Ultrawide | 20 mm | 20 mm | 2.2 | 106.2 | - | - |

| iPhone 15 Pro Max | Wide | 180 mm | 200 mm | 1.78 | 72.04 | - | - |

| iPhone 15 Pro Max | Tele | 900 mm | 1350 mm | 2.8 | 16.41 | - | - |

| iPhone 15 | Ultrawide | 100 mm | - | 2.4 | 106.56 | - | - |

| iPhone 15 | Wide | 100 mm | 150 mm | 1.6 | 68.16 | - | - |

| iPhone 14 Pro | Ultrawide | 20 mm | 20 mm | 2.2 | 106.2 | - | - |

| iPhone 14 Pro | Wide | 160 mm | 200 mm | 1.78 | 71.29 | 32.2 | - |

| iPhone 13 Pro | Ultrawide | - | 20 mm | 1.8 | 101.9 | 89.6 | 96.0 |

| iPhone 13 Pro | Wide | - | 150 mm | 1.5 | 67.1 | 33.6 | 21.5 |

| iPhone 13 Pro | Tele | - | -- | 2.8 | 25.2 | 25.2 | 15.1 |

| iPhone 12 Pro Max | Ultrawide | Not sharp at close Dist. | -- | 2.4 | 102.9 | - | - |

| iPhone 12 Pro Max | Wide | 120 mm | 150 mm | 1.6 | 67.7 | 32.3 | 21.5 |

| iPhone 12 Pro Max | Tele | Hard to get close | - | 2.2 | 30.1 | 32.3 | 15.1 |

| iPhone 12 Pro | Ultrawide | Not sharp at close Dist. | - | 2.4 | 102.9 | - | - |

| iPhone 12 Pro | Wide | 100 mm | 120 mm | 1.6 | 67.1 | 40.3 | 26.8 |

| iPhone 12 Pro | Tele | Hard to get close | - | 2.0 | 37.0 | - | - |

| iPhone 11 | Ultrawide | Not sharp at close Dist. | -- | 2.4 | 102.9 | - | - |

| iPhone 11 | Wide | - | 120 mm | 1.8 | 66.48 | 43 | 27.1 |

| iPhone XR | Wide | - | 120 mm | 1.8 | - | 36 | - |

| iPhone SE2 | Wide | - | 100 mm | 1.8 | - | - | - |

| iPhone 7 | Wide | - | 100 mm | 1.8 | 58.98 | 44.3 | 37.2 |

In general, the wide-angle cameras are the best to use except possibly the ultra-wide-angle camera on the iPhone 13 Pro. Newer wide-angle cameras have not led to higher resolution at close range if you look at Table 1. Changes in focal length and aperture have led to greater minimum focal distance during the years. For example, the resolution pixel per mm was better iPhone 7 than iPhone 13 Pro (Wide-angle)

However, the quality of the photos has improved significantly in recent years, there is a big difference in the photos from, for example, iPhone 7 and 11 (see examples at the bottom of the page). We still have 12 Megapixel sensors, but the pixels are much sharper today.

Comparison of photo quality between iPhone models

iPhone 7. Unsharp and problems with the white balance

iPhone 8. Unsharp and some problem with automatic white balance.

iPhone SE2. Sharper and better white balance than the older phones above.

iPhone XR. Similar result as iPhone SE2.

iPhone 11. Sharp. The quality is really good. Better than XR and SE2.

iPhone 12 Pro Max. The minimum focus distance is larger than for the ordinary 12 Pro and 11. It Is harder to get sharp images.

iPhone 13 Pro. UltraWide angle camera. Very sharp images. Will need special adjustments to avoid blurry edges.

iPhone 13 Pro. Wide angle camera. Not quite as good as 11,12 or 12 Pro.

Stitching images together

To be able to photograph the entire drill core, we need to take several pictures and stitch them together. The drill core is about 5 mm wide and 10-50 cm long. To get enough resolution, we need to photograph it at close range.

The challenge is that the minimum focus distance of the wide-angle camera is about 10-15 cm. This means that we can only photograph a small part of the drill core at a time. We need to take several overlapping pictures and stitch them together.

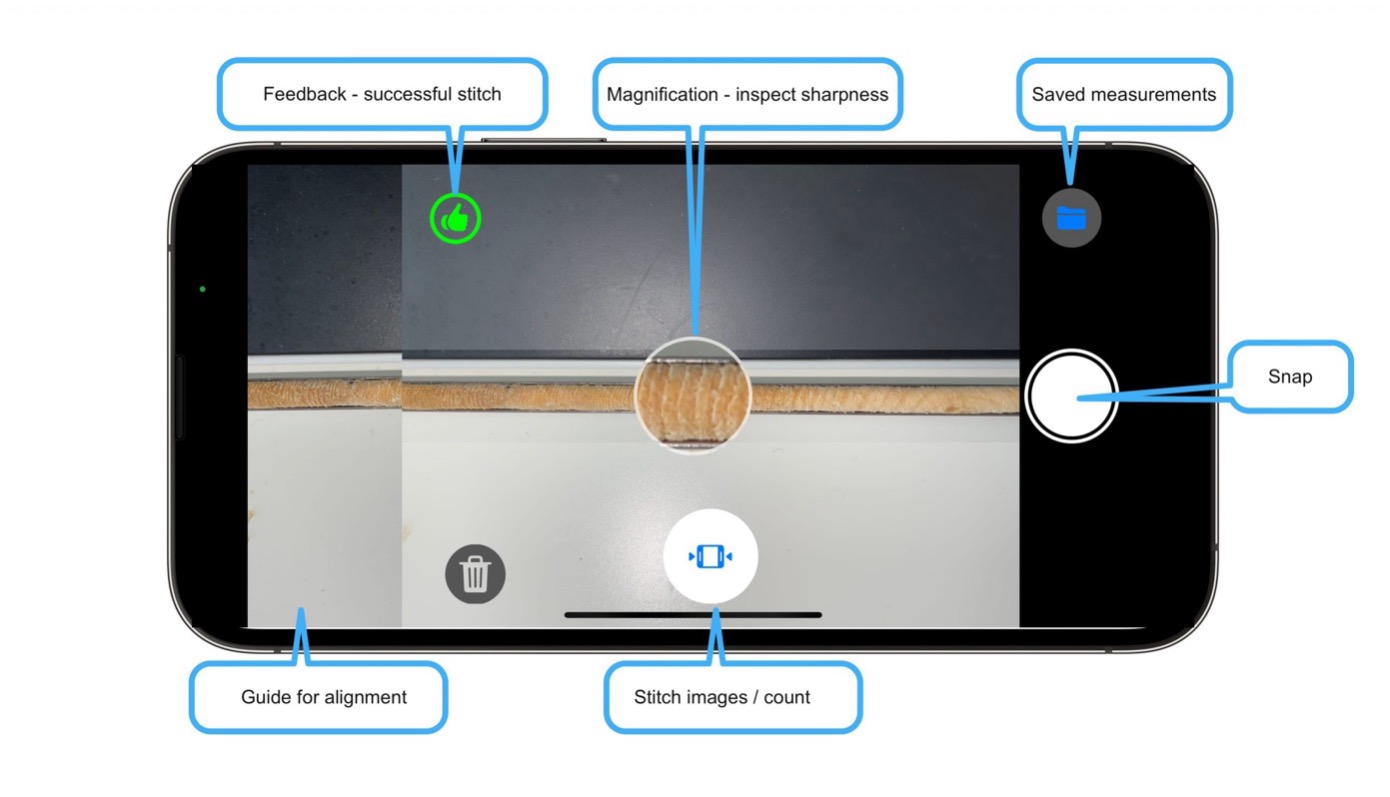

We have tested stitching images together and it works well. The user needs to take overlapping pictures and the app stitches them together automatically. We give the user feedback if the stitching was successful or if they need to retake the picture.

Visual guide showing the stitching process

Image quality

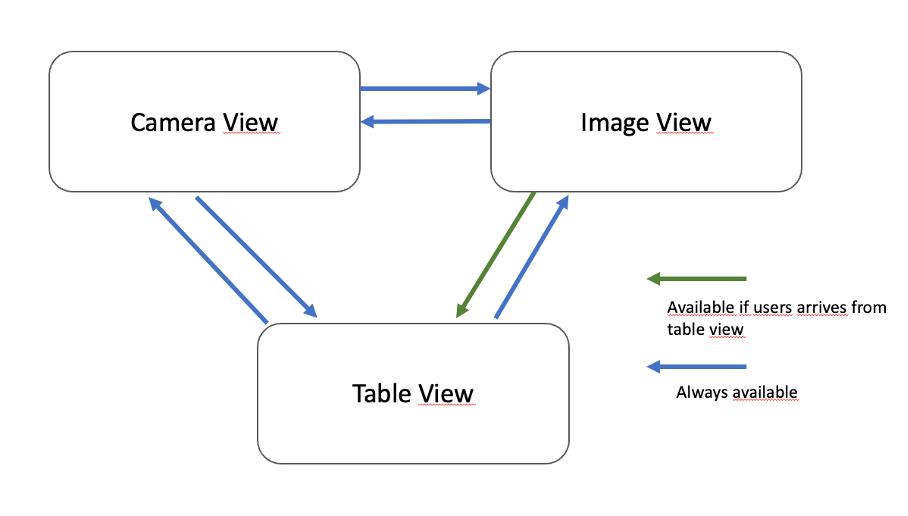

To be able to take the pictures with the highest possible quality, I want to be able to use the maximum size of the image sensor. The image sensor is 3000 x 4000 pixels. To be able to use maximum width (4000 px), the app must be used in landscape mode when photographing the drill core (Camera View). Then we have to build a screen where we can count the annual rings (Image view) and one where we can see the drill cores in a table (Table view).

Navigation between views

If you are out in the woods, you want to photograph annual rings and be able to check the photo quality and maybe count the annual ring. If you are in the office, you want to be able to look at previously photographed drill cores and count annual rings.

Therefore, we need to be able to navigate between the different views and here is a suggestion of what it might look like:

Navigation flow between different views

The Camera view needs to include the following:

- Graphic help to place the drill core in the middle of the screen.

- Show previously photographed image so that it is easier to photograph the drill core in the next image

- Feedback if it was a successful stitch.

- Be able to see if the image are sharp before pressing the shutter button.

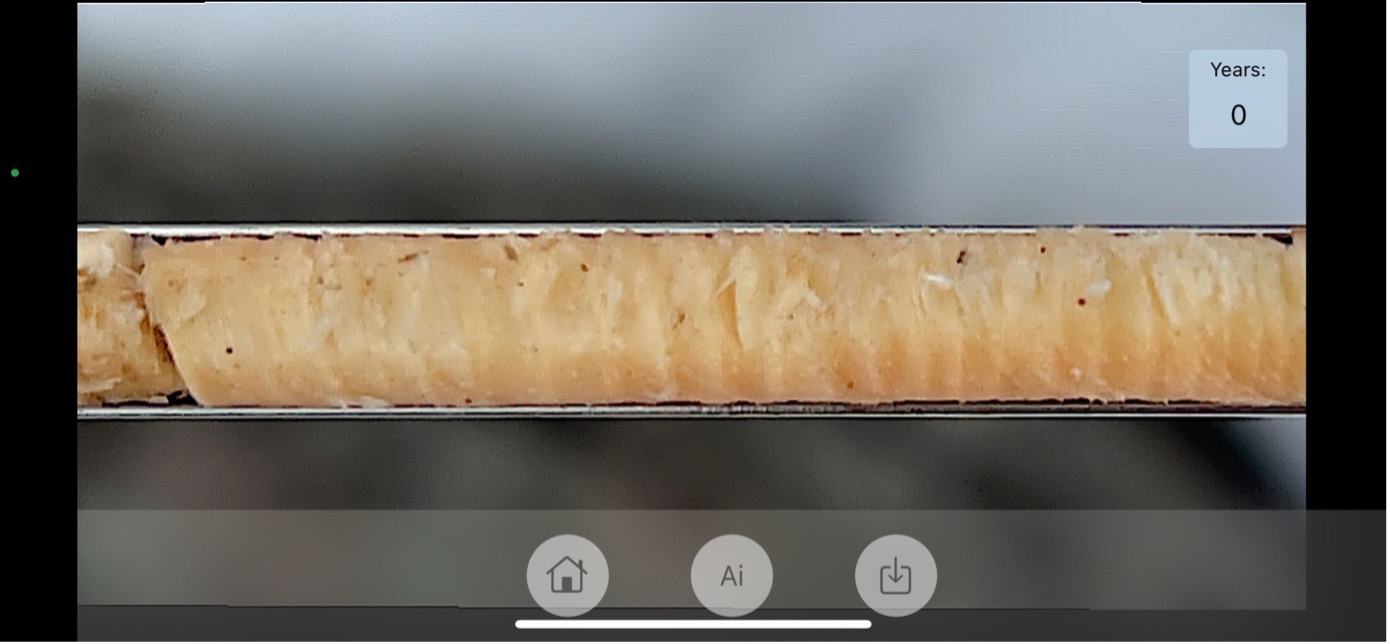

To be able to count the annual rings, the following is needed in the Image view:

- Be able to zoom into the image

- Count annual rings manually, mark every tenth annual ring and add up automatically.

- Be able to save the measurement.

The Table view

is should be a standard type where you can delete drill cores and select the one you want to look at in the Image View.

The next step is to test the app in the field and see if it works as expected. We will probably discover things that need to change.

Our schedule is to send out the app for testing at the end of March. Feel free to register your interest here.

If you missed our previous articles on how we created the app, feel free to read more:

Links to part 1 and 2.

Part 3: Why we abandoned the project

You may know that I have been working on an app to count annual rings on trees using your mobile. You may also have noticed that it has been rather quiet about this for a couple of weeks.

The reason is simple.

I was out testing it in reality and realized that it would not be possible to build such an app. I will now tell you why, so that if someone else tries this in the future, they can build on my experience.

Learning from failure

When you are surfing the web, almost everyone talks about their successful ventures, but few tell about when they fail. It makes you think that it is easy to succeed, but it also stops you from learning from other peoples mistakes. Success is a lousy teacher – failure is not. I am now going to tell you about what I learned and why I am now abandoning the idea.

The origin

It started several years ago, I heard a recurring problem that foresters thought it was cumbersome to count annual rings. They preferred a machine that could scan the age of the trees just by holding it up against the tree.

It is a difficult technical challenge to be able to look inside the tree without felling it. It felt beyond my ability. But it maybe would be possible to photograph drill cores with a telephone and then let the phone count the annual rings itself.

I started building an app to be able to photograph drill cores in a first step and count them manually. If successful, the next step would be to build an AI solution that counts them automatically.

The first challenge

was to get close enough, but this could be solved by taking several photographs and then stitching them automatically. It was a bit difficult because the autofocus had a hard time focusing on a narrow drill core. But I solved it by doing a magnification function that showed if the drill core was sharp or not. If the user held a hand behind the drill core, it all went well.

The second challenge

was to stitch the images - the user had to have a fair amount of overlap between the images. Not too little, because then it did not manage to stitch and not too much because then the user would have to take too many pictures. I solved it by showing a fair amount of the previous image and giving the user feedback if it managed to stitch the new image with the old image or if it needed to be redone. By using haptic feedback, it became clear whether one succeeded or failed.

I tested indoors and felt I had something going on.

Then I went outdoors a few times and learned the following:

- The light was a challenge, sunlight and snow created much contrast in the image.

- The annual rings were not clearly visible in the pictures. It was hard to be really sure if it was spring wood or summer wood.

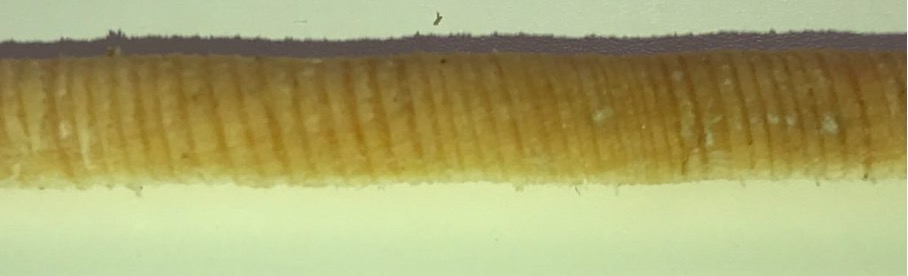

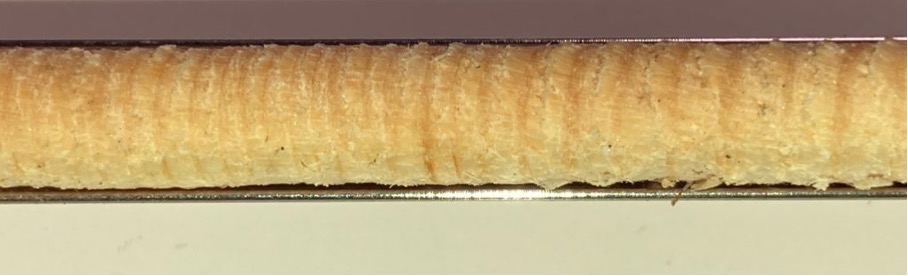

Image 1: Drill core from Pine. It is hard to count the annual rings.

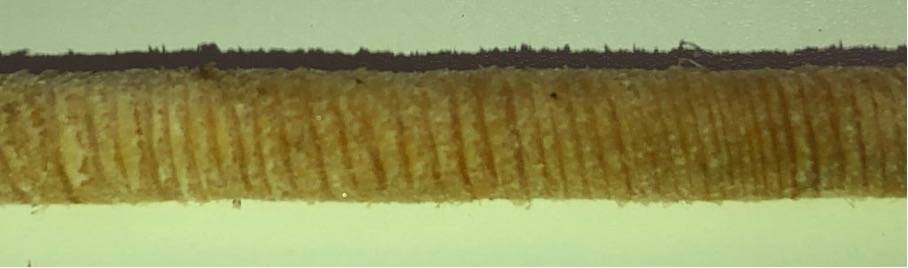

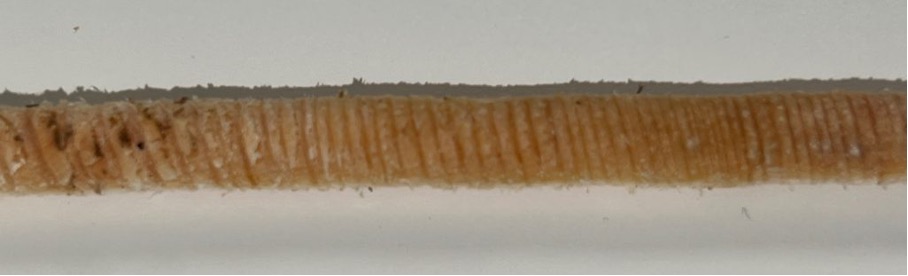

Image 2: Drill core from Pine. You often get dirt on the drill core. It sometimes makes it harder to count and will make automatic counting even harder.

The problem with the light, could be solved if you made sure to have the sun in the back and have as little snow in the picture as possible.

I did not solve the problem with the annual rings not being good enough. The resolution was quite high, 20-40 pixels per mm. But the sharpness was not razor sharp and the contrast between the annual rings too low. I tried to increase the contrast and apply different amounts of sharpness in the image. But it still did not turn out well enough. This really felt like a crucial problem. The problem mostly occurred in the outer part of the image and it could partly be an optical issue.

The desktop annual ring software that are available on the market often require the analysis of cut wood that are polished. Drill cores are not as good a material to use, and that is probably the main reason why it was so difficult.

Avoiding bark residues on the drill core is not easy, it usually happens for pines that have thick bark. Peeling off this was difficult and you risked losing the drill core while doing so. In addition, it would be a challenge to let an AI distinguish between the dark summer wood and dirt.

What made me finally give up was when I was standing out in the woods, struggling to take overlapping pictures. When I finally succeeded, I had a hard time seeing the annual rings. I switched to counting them manually and it was faster. If I have problems with my own app, then what should the experience not be like for another user?

Lessons learned

I learned a lot, including the following:

- There is always a risk associated when you create new products. You must try to minimize the risk by testing the critical parts first. In this case, it was the photo quality.

- Interest has been lower than expected. Few people have shown interest. This indicates that the market for such an app is not large. If you build a great app on a small market, it is hard to keep it viable.

- Don't hesitate to give up even though you have invested a lot of time in a project. It is better to test a lot of ideas and choose the one that get most success and traction. Now I have more time to spend on my other ideas...

Part 4: Revisiting the project 3 years later

During the years that have followed, there has been some interest in the subject. There has also been some improvements in the cameras on the phones and there has also been some interesting publications in the area.

Over the last five years, automated tree-ring detection has rapidly evolved from fragile, rule-based image processing toward robust deep-learning approaches. Early progress came from applying convolutional neural networks to ring-boundary segmentation, enabling far greater tolerance to noise, uneven sanding, and variable lighting. A major milestone was the use of instance-segmentation models such as Mask R-CNN to detect annual ring boundaries in both scanner and smartphone images (Kim et al., 2023). Shortly after, fully automated pipelines emerged that combine deep learning with post-processing and export to standard dendrochronology formats (Poláček et al., 2023). These methods were accompanied by open-source implementations, making state-of-the-art ring detection reproducible and accessible (TRG-ImageProcessing on GitHub). More recently, new annotated datasets and semantic-segmentation baselines have been released to address challenging hardwood surfaces and rough samples (Wu et al., 2024). Transformer-based segmentation models have also been applied to high-resolution wood microsections, improving boundary delineation in anatomically complex samples (García-Hidalgo et al., 2024). At the same time, large foundation segmentation models have lowered the barrier to interactive annotation and rapid prototyping (Kirillov et al., 2023). The open-source release of these models has accelerated experimentation across research and applied product development (Segment Anything on GitHub). Together, these advances now make high-precision, automated ring counting from photographs a realistic foundation for field-ready and mobile applications.

We have added the data for the last iPhone lenses and cameras in the lists

We look forward to see where all this will end